Pre-trial Solitary Confinement – Extortion to Inflict Psychological Pain

Solitary Confinement – The Invisible Torture

Humans are social animals; deprived of regular contact, we lose our minds. First, let me note that solitary confinement has historically been a part of torture protocols. It was well documented in South Africa, Eastern Europe and China. It’s been used to torture prisoners of war all over the world

There are a couple of reasons why solitary confinement is typically used. One is that it’s a very painful experience. People experience isolation panic. They have a difficult time coping psychologically with the experience of being completely alone.

In addition, solitary confinement imposes conditions of social and perceptual stimulus deprivation. Often it’s the deprivation of activity – the deprivation of cognitive stimulation – which some people find to be painful and frightening.

Some of them lose their grasp of their identity. Who we are and how we function in the world around us, is very much nested in our relationship with other people. Over a long period of time, solitary confinement undermines one’s sense of self. It undermines your ability to register and regulate emotion. The appropriateness of what you’re thinking and feeling is difficult to index because we’re so dependent on contact with others for that feedback. And for some people, it becomes a struggle to maintain sanity.

That leads to the other reason why solitary is so often a part of torture protocols. When people’s sense of themselves is placed in jeopardy, they are more malleable and more easily manipulated. In a certain sense, solitary confinement is thought to enhance the effectiveness of other torture techniques.

When Charles Dickens toured the United States in 1842, he witnessed solitary confinement at Eastern State Penitentiary outside Philadelphia, and wrote about it in his travelogue, “American Notes for General Circulation.”

“I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for months and years, inflicts upon the sufferers; and in guessing at it myself, and in reasoning from what I have seen written upon their faces, and what to my certain knowledge they feel within, I am only the more convinced that there is a depth of terrible endurance in which none but the sufferers themselves can fathom, and which no man has a right to inflict upon his fellow-creature. I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body; and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore the more I denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.”

This observation was made nearly one hundred and sixty years ago. Solitary confinement, during pre-trial detention, is still in use in Denmark today; although it has been restricted to a short period, it shames the Danish justice system.

My solitary confinement

The Danish authorities concerted to set about destroying my business. Bagmandspolitiet worked overtime to vilify and destroy my person and business. What is worse, they concerted to destroy me by their pre-trial punishment. In 1980 when the late Minister of Justice, Erik Ninn-Hansen, spoke about solitary confinement, he acknowledged that it was a form of torture. Bagmandspolitiet and the courts knew the “effectiveness” of this mental torture.

The worst feeling about my solitary confinement was the unknown with regards to how long I would remain in solitary confinement. When every minute you have to surrender to the fact that you are locked up every minute and there is obviously nothing you can do about it, you start believing that they (the authorities) can do anything they like and there is no law. In the beginning, you have hope, then less and less; and ultimately after many months you give up hope, you become totally powerless.

It was worse because I was not “mentally” prepared for the solitary confinement and I had, as a result, a much greater trauma. I had always been my own boss, did not go to the military and enjoyed a comfortable life with total freedom, having choices and money.

When I say mentally prepared, I relate more to the fact that if I lived in Russia, DDR or another totalitarian country or if I was a prisoner of war in Vietnam, I would know what could happen if you were arrested. Under such conditions, our mind is somewhat able to adjust to much more pressure.

The reality: In the first months I witnessed daily that I was losing out in taking financial advantage of the market; in addition to witnessing that the Bagmandspolitiet destroyed my companies and my life including everything I had worked for as well as the fact that my family was being destroyed day by day by the Special Prosecution. (See my letters to Judge Claus Larsen when I started my hunger strike:

Bagmandspolitiet directly prevented me from having my complaint about my long solitary confinement and treatment dealt with by the European Commission of Human Rights. My complain of torture under Article 3.

Bagmandspolitiet kept a letter for more than two years away from showing me; totally contemptuous of the Convention as I was allow free uncensored communication in accordance of the European Convention of Human Right.

There can be no doubt in my and my lawyers s at the time that this was a deliberate act as the Danish authorities did not want my treatment to be subject to a case at the European Court.

When I sent my first letter and application to the ECHR in August 1980 and did not hear anything for more than two years and 2 month, I felt that something had happened, but I did not know that Bagmandspolitiet had kept the letter away from me and my defence lawyers.

The fact, that I did not know about the letter in September 1980, prevented me to follow up and ultimate from the Commission dealing with my horrendous solitary confinement treatment by the Danish authorities.

Bagmandspolitiet still opened other letters from ECHR, when I complained they just laughed.

In my solitary confinement during the summer months of 1980, I did not speak a word to anyone; at the same time, I could hear the children from the nearby playground, where I played myself as a child. To make matters worse, the sound from a nearby kindergarten, where I heard the voices of happy children at a time where I was locked up in a cold cell with stone floors and little daylight.

You see no other person in solitary confinement, only the prison guard because I had refused to take a daily walk outside. Inside a cage smaller than anything allowed for the animals in the zoo, sometimes for weeks and even months I really had no contact at all with other humans (although prison guards can also be human). I would only go to the bathroom and toilet, but I did that without speaking or indeed looking at the guards which at the time I felt a total contempt for. Moreover, I refused to be served food (since I even thought they would poison me), I purchased my own food which I kept in the cold prison cell and unpacked myself.

When I left the solitary confinement, I had lost my hope, dreams and appetite for life.

After being in Solitary confinement one becomes unengaged with emotions stripped from all human dignity

When again and again people have been subject to injustice and tragedy, at some point one somewhat comes to disregard one’s feelings and surroundings.

You can only reach the bottom of despair after which there is really nothing that can hurt; one becomes unengaged with emotions stripped from all human dignity.

I consider the unlawful methods used and the abuse of power and injustice, which my loved ones and I have been subjected to, to be of the same character and disposition which sent people to concentrations camps forty years earlier and at the time in Russia. I believe that I would not be moved emotionally if the door to my torture cell was opened and they told me: Hauschildt you will now go to the torture chamber or you have been given a thirty years sentence. I do understand the poor people in the Gulag of injustices.”

In writing this, I did not know that I would remain in my pre-trial torture cell for another nine months after that, not seeing my wife, sons and mother sometimes for so many months. Moreover, remain in pre-trial detentions for more than four years.

My disgust and aversion towards Bagmandspolitiet at the time, also to the prison guards, made my life even more difficult since it left me alone for weeks – alone with my own thoughts and apprehensions.

Yes, I did do something unlawful from my solitary confinement in a moment of madness

I did indeed commit various unlawful acts, even so-called “criminal acts”, like giving instructions to my wife to go abroad and get help from lawyers, money; and later asking her for help to get me out from prison. After all, my wife could legally go abroad and indeed secure the companies and our family’s assets and more importantly, instruct and pay lawyers to assist. Most of these instructions were made during my solitary confinement and some shortly thereafter, all very normal. Moreover, my companies and assets abroad could not legally be seized, however, due to my wife’s inaction, the greedy Danish liquidators successfully got hold of some of these assets abroad.

One could claim that these instructions “broke the Danish law”, despite that the claims I made was against my own companies abroad and companies which were solvent at the time, moreover, assets which I later did receive. Nevertheless, the claims and actions can be seen as ridiculous and on reflection, just what everyone could expect from a broken-down person in solitary confinement. All action was a result of my mental state and hopelessness at the time.

I simply had to do something; I saw all the actions taken against me by Bagmandspolitiet as unlawful, political and criminal since I was innocent.

When you face so much injustice, you somehow feel inclined to do something and to take some kind of action, even which can be considered stupid later after doing it. Solitary confinement for months on end is torture and your mental capacity changes as a result. I planned all sorts of actions, but nothing serious.

How low and ridiculous Bagmandspolitiet became when it prosecuted me for actions which I had participated in long into my solitary confinement. Any psychiatrist would have declared me mentally ill and not responsible and indeed unfit even for trial; moreover, my actions had only been to write instructions to my wife, mostly instructions which she did not carry out.

The solitary confinement just distorted everything including my mental ability to think straight, and even worse – to concentrate. When my lawyer went away on holiday and had other matters to attend to, in March/April 1980, I did not speak to any person for weeks and after a month I found that I had lost my voice and could not speak.

The Special Prosecution took full advantage of using psychological methods, like instructing that without any warning, I was always brought straight to a courtroom or a meeting at their offices so that I would be shaken, disoriented and confused. They also instructed, at any time searches of the cell, where several people certainly would enter my little space. Like the colleagues in Stasi and KGB, they knew all the tricks of the trade. (See: “Bagmandspolitiet Used Zersetzung on Me” )

Frankly, I was very shaken and found coming from solitary confinement straight into a room with people (in fact anyone), to be chaotic every time which was so overwhelming as well as a frightening experience for me.

Whereas people that are in pre-trial detention solitary confinement in Denmark now (see Rodhe vs. Denmark 2005), receive regular visits by various people such as prison teachers, the chaplain, welfare officers all in addition to having regular medical inspections. Moreover, they are allowed to use the fitness room (gym) and receive tuition and even having the use of a physiotherapist. Their cell contains television and a refrigerator/freezing compartment.

I did not have any of this happening to me, none so ever. In stating this, it is only fair to say that I could have asked to see the prison chaplain or a medical doctor, but I simply did not trust nor did I want to speak to these people at the time. I did not speak to them for months. First, when I went on a hunger strike and refused food, only taking water, the doctors did visit me and took urine samples. Ultimately, the doctors ordered me to the hospital department.

Most people read about hunger strikes and truly have no idea about how difficult it is. The human body will fight every moment, every hour and day against the human will. To refuse food is not only against our natural instinct but very difficult as one have every moment to overcome oneself. I only took water and 2 vitamin tablets. In the end, I had to tie a scarf around my fingers to remind myself to drink water, you do not feel thirsty or anything.

After being alone over a long period, even to speak to people become a problem. It is characteristic that Rodhe asked to stay in solitary confinement after his long incarceration – this is quite normal because other people close to you become frightening and you want to be left alone. You can practically feel their space and it can be very overwhelming.

The people working in prison and the prison environment slowly destroy your humanity. I registered that I had been personally subject to nearly one thousand searches during the years; when you are undressed regularly and everything you have is searched and gone through, your humanity slowly disappears and apathy takes over. These searches break down your dignity.

The prosecution or the prison guards could come and go through everything at any time, everything you have written down, everything you have in your Spartan cell. This random search is part of the process to break you down and make you amenable.

Dignity had slowly but steadily run into the sand and I was left without any my dignity, gone forever. Privacy is an inherent human right and a requirement for maintaining the human condition with dignity and respect.

When you are stripped from all dignity and locked up in a cell with cold walls, hearing screams from others either crying out in their misery or being beaten by prison guards and you can’t do anything – your humanity slowly disappears.

In pre-trial solitary confinement I remained vulnerable against the unjustifiable parasitic strains of the Danish tabloid press.

Mogens Hauschildt

When you face so much injustice, you somehow feel good to do something and to take some kind of action, even an action which can be considered stupid at the time when you look back later on. Solitary confinement for months on end is torture and your mental capacity changes as a result.

The actions I took where: two hunger strikes (one for seventeen days and the other for fifty-five days, just drinking water) and writing ridiculous instructions to my wife which I later was prosecuted for. I lost more than fifty-seven kilograms in weight; when I was arrested my weight was one hundred and twenty kilograms and after my last hunger strike it was sixty-seven kilograms.

It was worse to be in solitary confinement in Denmark because I was not “mentally” prepared for the solitary confinement; I had, as a result, a much greater trauma. When I say mentally prepared, I relate to the fact that if I lived in Russia or another totalitarian country or if I was a prisoner of war in Vietnam, I would know what could happen if you were arrested. Under such conditions, our mind is somewhat able to adjust to much more pressure.

I knew that I was innocent and in the first few months of my solitary confinement, not only did I lose out a large amount of money daily, everything I had worked for and my family was being destroyed day by day by the Special Prosecution.

In my solitary confinement during the summer months of 1980, I did not speak a word to any person; at the same time I could hear the children from the nearby playground (where I myself played football as child), and even worse, the sound from a nearby kindergarten where I heard the voices of happy children – I love children

I did not want to show to the Special Prosecution or the court that they could break me down by all their actions and injustices. Moreover, I did not want to show my family and sons what had happened to me.

Therefore I suppressed a lot of traumatic experience at the time. To make matters worse, I was never allowed a proper diagnosis and treatment. Since it was obvious that I suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), after my solitary confinement – having been subjected to psychological trauma – getting treatment as soon as possible after PTSD symptoms developed could prevent PTSD from becoming a long-term condition.

“The effect of solitary confinement on the mind of a person charged with a crime may be imagined.

It is a well-known psychological fact that men and women have frequently confessed to crimes which they did not commit”

– The Washington Supreme Court 1910

My defence lawyers and I asked the court on many occasion for permission for me to see a respected Danish psychiatrist Mogens Jacobsen. Through the more than four years, the courts and the prosecution did not want me to get “outside” help; they simply did not want me to expose what had happened to me and the “mental scars” from the invisible torture. Mental scars which really made me unfit to stand trial.

No psychological or psychiatric examination was carried out on me during the more than four years of pre-trial detention.

The fact that the Danish authorities (Ministry of Justice, courts and prosecutions) did not permit me outside help and treatment during my long incarceration, caused me to suffer from the following: severe stress symptoms, reoccurring nightmares and flashbacks, panic attacks, extreme agitation and irritability, amnesia and severe anxiety, migraines, severe depression and feelings of worthlessness.

I possibly also suffered from bipolar disorder (also known as manic depression) which involves abnormally “high” or pressured mood states, known as mania or hypomania, alternating with normal or depressed moods. At times all of this can overwhelm me and my ability to cope. I still have increased arousal and therefore difficulty in falling and staying asleep, and have hypervigilance at times. All this was an effect of psychological trauma during my long pre-trial solitary confinement.

New research has revealed how severe trauma can produce long-term changes in the nerves in the brain. In particular, it is now believed that the problem is caused by alterations in the chemical substances that nerves in the brain use to communicate with each other, substances referred to as neurotransmitters.

These alterations in neurotransmitters may be responsible for the symptoms and behaviours. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder has therefore shifted to drugs that target these chemical substances. Unfortunately, however, side effects interfered with the long-term use of these drugs; moreover, they do have considerable effects on one’s ability to live a normal life. New research shows that a person’s normal capacity can be reduced by up to 50%.

I organised a general complaint to the European Commission of Human Rights in 1983 signed by hundreds of former prisoners who had been subject to pre-trial solitary confinement.

Despite speaking out against pre-trial solitary confinement in political opposition and working as a defence lawyer some years earlier, when he became Minister of Justice Erik Ninn-Hansen had no opinion and would not comment on this torture. Neither did he do anything to change this.

Some of the best descriptions of the effects of solitary confinement I find in the World Health Organisation writes about solitary confinement. I have experienced most of the effects mention below.

Prisons and Health

“Three main factors are inherent in all solitary confinement regimes: social isolation, reduced activity and environmental input, and loss of autonomy and control over almost all aspects of daily life. Each of these factors is potentially distressing. Together they create a potent and toxic mix, the effects of which were well summarized as early as 1861 by the Chief Medical Officer at the Fremantle Convict Establishment in Western Australia:

In a medical point of view I think there can be no question but that separate or solitary confinement acts injuriously, from first to last, on the health and constitution of anybody subjected to it … the symptoms of its pernicious constitutional influence being consecutively pallor, depression, debility, infirmity of intellect, and bodily decay.

The rich body of literature that has accumulated since that time on the effects on the health of solitary confinement largely echoes these observations and includes anxiety, depression, anger, cognitive disturbances, perceptual distortions, paranoia and psychosis among other symptoms resulting from solitary confinement. Levels of self-harm and suicide, which are already much higher among prisoners than in the general population, rise even further in segregation units.

The effects on the health of solitary confinement include physiological signs and symptoms, such as:

Psychological symptoms occur in the following areas and range from acute to chronic: anxiety, ranging from feelings often tension to full-blown panic attacks:

-

- persistent low level of stress;

- irritability or anxiety;

- fear of impending death;

- panic attacks;

- depression, varying from low mood to clinical depression:

- emotional flatness/blunting;

- emotional liability (mood swings);

- hopelessness;

- social withdrawal,

- loss of initiation of activity or ideas, apathy, lethargy;

- major depression; •

- anger, from irritability to rage:

- irritability and hostility

- poor impulse control;

- outbursts of physical and verbal violence against others, self and objects;

- unprovoked anger, sometimes manifesting as rage;

- cognitive disturbances, ranging from lack of concentration to confused states:

- short attention span;

- poor concentration;

- poor memory;

- confused thought processes, disorientation;

- perceptual distortions, ranging from hypersensitivity to hallucinations:

- hypersensitivity to noises and smells;

- distortions in time and space;

- depersonalization, detachment from reality;

- hallucinations affecting all five senses (for example, hallucinations of objects or people appearing in the cell, or hearing voices);

- Paranoia and psychosis, ranging from obsessional thoughts to full-blown psychosis:

- recurrent and persistent thoughts (ruminations)

- often of a violent and vengeful character (for example, directed against prison staff);

- paranoid ideas, often persecutory;

- psychotic episodes or states: psychotic depression,

- schizophrenia;

- self-harm and suicide.

How individuals will react to the experience of being isolated from the company of others depends on personal, environmental and institutional factors, including their individual histories, the conditions in which they are held, the regime provisions which they can access, the degree and form of human contact they can enjoy and the context of their confinement.

Research has also shown that both the duration of solitary confinement and uncertainty as to the length of time the individual can expect to spend in solitary confinement promote a sense of helplessness and increase hostility and aggression.

These are important determinants of the extent of adverse health effects experienced.

-

- gastro-intestinal and

- genito-urinary problems

- diaphoresis

- insomnia

- deterioration of eyesight

- lethargy

- weakness

- profound fatigue

- feeling cold

- heart palpitations

- migraine headaches

- back and other joint pains

- poor appetite,

- weight loss

- diarrhoea

- tremulousness

- aggravation of pre-existing medical problems.

Many books and pages have been written about solitary confinement, including its use in Denmark on pre-trial prisoners. During my time as a spokesman for the prisoners, I collected a large amount of material which we then submitted to The European Commission of Human Rights in 1982. Unfortunately, nothing happened at the time despite the clear evidence that solitary confinement is invisible torture.

Solitary confinement in Danish prisons has received substantial international criticism. Amnesty International criticised Denmark in 1980 (after my application to the Commission) and in 1983. These criticisms have grown stronger after 1990 especially from the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) and the Committee against Torture (CAT). The CPT visited Denmark in 1990, 1996 and 2002, critically raising issues concerning solitary confinement each time.

When I was the spokesman for the prisoners, I did participate in the early work of the “Isolation Group”. Interestingly, several studies have been carried out in Scandinavia on the effect of solitary confinement later on; I have never been contacted nor have I participated in such studies.

The Convention Against Torture was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1984 and came into force in 1987. Article 1 of the Convention stipulates that:

For the purpose of this Convention, the term “torture” means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person..

Regrettably, the judgment by the ECHR in 2005 as to Denmark’s use of pre-trial solitary confinement in the Peter Rohde case cannot be considered fair or right. This judgment was made with only seven judges and not the full seventeen court judges; this was not really proper considering the importance of the whole issue. Four judges voted for Denmark (including the Danish), and three judges against Denmark, judging that Denmark had indeed contravened Article 3. So four judges against three – not a great win for Denmark.

Everyone reading this judgement should read the Joint Dissenting Opinions of Judges Rozakis, Loucaides and Tulkens. Christos Rozakis was President Judge in charge when the Commission considered Erik Ninn-Hansen case and found it to be inadmissible in 1995.

Unfortunately, I did not follow this case and did not know about the whole affair at the time otherwise I certainly would have supported the applicant. Later on, I will deal with various issues of this case and how I see the large difference between my solitary confinement in 1980 and that of Peter Rohde in 1995.

I do not believe today that the ECHR will make any serious judgment against Denmark, considering the profound changes to the membership of the European Council during the last twenty years with countries such as Moldova, Russia, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan.

As to the use of solitary confinement in general and particularly Denmark’s use of pre-trial solitary confinement, I should like to mention Peter Scharff Smith, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute of Human Rights, who has done a lot of research on the subject of solitary confinement.

In the book “Crime and Justice” A Review of Research, edited by Michael Tonry, Volume 34, published in 1996 by The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, Peter Scharff Smith write:

The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates

The evidence strongly suggests that the use of solitary confinement during the early phases of imprisonment increases the suicide risk and most likely also raises the likelihood of incidents of self-mutilation.

The Practice of Solitary Confinement – as Extortion

<p”>It is illegal, according to Danish law, to use solitary confinement and pre-trial detention as extortion to coerce suspects into confessing or pleading guilty. It has nevertheless often been claimed that the element of extortion often is very real-both as a motive (for the authorities) and as a reality (for the imprisoned).</p”>

In 1980, the later Danish minister of justice and the defence attorney and member of the Conservative people’s party, Erik Ninn-Hansen (former speaker of the parliament and longest-serving member), for example, stated: “that solitary confinement today is used less to avoid detainees from communicating with others and more to squeeze out a confession.” Ninn-Hansen observed that “solitary confinement is a commodity” and remand prisoners could free themselves from isolation at the price of a confession (Politiken 1980, p. 3; translated by the author).

Many other defence attorneys have claimed the same thing: that pre-trial detention – and especially isolation – in reality, is sometimes or often used as extortion (Petersen 1998, p. 34; Stagetorn 2003, p. 38). In 2000, for example, the Danish defence attorney Manfred Petersen asserted that “solitary confinement is a form of pressure in order to obtain information and/or a confession” (quoted from Thelle and Traeholt [2003, p. 772]).

Professor Rod Morgan, who has assisted the CPT (European Committee for the Prevention of Torture) has pointed to an unfortunate relationship between prisoner confessions and the termination of their isolation. Professor Morgan has written critically of the “Scandinavian way” – the isolation of remand prisoners – which he describes as “reckless” and allowing the police “extreme powers to exploit” (Morgan 1999, p. 204).

He concludes that pre-trial isolation can be “severely painful” but also seeks to know whether or not “it is purposefully imposed with a view to eliciting confessions, intelligence and other evidence? It is at this point that legal casuistry comes into play. The answer must technically be no – but in practice, the answer is sometimes almost certainly yes” (p. 202).

In other parts of the world, the use of pre-trial solitary confinement has long been a well-known extortion technique to inflict psychological pain on remand prisoners in order to force out a confession. This was, for example, the case in the Soviet Union and in South Africa during apartheid (Hinkle and Wolff 1956; Riekert 1985; West 1985; Foster, Davis, and Sandler 1987; Veriava 1989).

Communist methods have been analysed as follows: “When the initial period of imprisonment is one of total isolation, such as used by the KGB, the complete separation of the prisoner from the companionship and support of others, his utter loneliness, and his prolonged uncertainty have a further disorganizing effect upon him … He becomes malleable … and in some instances, he may confabulate. The interrogator [then] exploits the prisoner’s need for companionship.” (Hinkle and Wolf 1956, p, 173).

It was for similar reasons that are, “the effectiveness of indefinite detention and solitary confinement in provoking anxiety and psychiatric instability” – the CIA included [these methods].

Among its principal techniques of coercion are now in repudiated manuals on interrogation from the 1960’s” (Brief of Amici Curiae Human Rights First et al., Hamadan v. Rumsfeld, 546 U.S. 05-184 [2005], p. 5).

The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison

The health effects of solitary confinement

Extracts from Pages 500, 501, 502, 503 and 504

“Crime and Justice” published in 1996 by The University of Chicago Press, Peter Scharff Smith writes:

As described from the inmate point of view by a South African remand prisoner, “One morning you get up and say to yourself, I’m not going to stand for this anymore, I am going to tell them, I’m going to give evidence, providing they just let me out. You’re prepared to do anything to get’ out of that condition of solitary confinement” (Foster, Davis, and Sandler 1987, p. 140; see also Dr Louis West’s report “Effects of Isolation on the Evidence of Detainees” in Bell and Mackie [1985, p, 69]).

In 1910, the same pre-trial effect of solitary confinement was clearly by the Washington Supreme Court: “The effect of solitary confinement on the mind of a person charged with a crime may be imagined. It is a well-known psychological fact that men and women have frequently confessed to crimes which they did not commit. They have done it, sometimes to escape present punishment which had become torture to them; sometimes through other motives” (State v. Miller, 61 Wash. 125, 111 Pac. 1053 [1910]; here quoted from Haney and Lynch [1997, p. 486]).

According to Professor Don Foster and colleagues, “There seems little doubt that solitary confinement for purposes of interrogation, indoctrination or information extraction does have aversive effects and should be regarded as a form of torture” (Foster, Davis, and Sandler 1987, P. 68).

D. Remand Prisoners’ Inability to Defend Themselves Legally

An obvious problem connected with the isolation of pre-trial detainees is that solitary confinement hampers their ability to function properly and thereby defend themselves. When remand prisoners suffer some of the above-mentioned health effects, they are less able to speak coherently and thereby to assist their lawyers in preparing a sensible defence. This, of course, constitutes a direct attack on their most basic legal rights.

V. Conclusion

Solitary confinement can have serious psychological, psychiatric, and sometimes physiological effects on many prison inmates. A long list of possible symptoms from insomnia and confusion to hallucinations and outright insanity has been documented.

A number of studies identify a distinguishable isolation syndrome, but there is no general agreement on this. Research suggests that between one-third and more than ninety per cent experience adverse symptoms in solitary confinement and a significant amount of this suffering is caused or worsened by solitary confinement. The conditions of solitary confinement very likely influence the level of distress suffered. The U.S. Supermax prisons could be one of the most harmful isolation practices currently in operation.

The allocation of mentally ill inmates to Supermax prisons (and sometimes to other places of punitive or administrative segregation) is likely to be high, but the prevalence of adverse psychological symptoms in some Supermax prisons is clearly significantly higher than even high base expectancy rates for mental illness.

Very different individual reactions to solitary confinement are clearly possible. Some people cope much better than others in isolation. According to some researchers, some inmates can handle even prolonged solitary confinement without displaying any serious adverse symptoms.

Still, the overall conclusion must be that solitary confinement – regardless of specific conditions and regardless of time and place – causes serious health problems for a significant number of inmates. The central harmful feature is that it reduces meaningful social contact to an absolute minimum: a level of social and psychological stimulus that many individuals will experience as insufficient to remain reasonable.

Healthy and relatively well-functioning prisoners in general prison populations suffer from a high rate of psychiatric morbidity and health problems (inside and outside of prisons), but solitary confinement creates significant additional strain and additional health problems. This was the case in the nineteenth century where Pennsylvania model prisons experienced serious problems with the health of inmates – problems not experienced in the same manner or with the same intensity in Auburn model prisons. The same difference has been documented in contemporary prisons by studies conducted throughout the last approximately thirty years.

A recent article in the Guardian newspaper made reference to a 12 year old study: A study involving extensive interviews with people held in the security housing units at Pelican Bay prison in northern California in 1993 found that solitary confinement induces a psychiatric disorder characterised by hypersensitivity to external stimuli: hallucinations, panic attacks, cognitive, deficits, obsessive thinking, paranoia and a litany of other physical and psychological problems. Psychological assessments of men in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay indicated high rates of anxiety, nervousness, obsessive rumination, anger, violent fantasies, nightmares, trouble sleeping, as well as dizziness, perspiring hands and heart palpitations.

Testifying before the California Assembly’s public safety committee in August 2011, Dr Craig Haney discussed the effects of solitary confinement. “In short, prisoners in these units complain of chronic and overwhelming feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and depression,” he said. “Rates of suicide in the California lockup units are by far the highest in any prison housing units anywhere in the country. Many people held in the SHUs become deeply and unshakably paranoid, and are profoundly anxious around and afraid of people [on those rare occasions when they are allowed contact with them]. Some begin to lose their grasp on their sanity and badly decompensate.

Psychological effects?

In a recent article in Wired magazine (https://www.wired.com/2013/07/solitary-confinement-2/) headed:

The Horrible Psychology of Solitary Confinement

The human brain is ill-adapted to such conditions, and activists and some psychologists equate it to torture. Solitary confinement isn’t merely uncomfortable, they say, but such an anathema to human needs that it often drives prisoners mad.

In isolation, people become anxious and angry, prone to hallucinations and wild mood swings, and unable to control their impulses. The problems are even worse in people predisposed to mental illness and can wreak long-lasting changes in prisoners’ minds.

“What we’ve found is that a series of symptoms occur almost universally. They are so common that it’s something of a syndrome,” said psychiatrist Terry Kupers of the Wright Institute, a prominent critic of solitary confinement. “I’m afraid we’re talking about permanent damage.”

Use of solitary confinement in remand prisons can in some ways be considered even worse than the practice of isolating sentenced prisoners.

The psychologically stressful and dangerous first two weeks of imprisonment and the disturbing suicide rates in remand prisons illustrate this. The element of effective coercion of guilty pleas from the isolated prisoners is another. The coercion problem, which Rod Morgan compares to “moderate psychological pressure,” makes isolation of remand prisoners a dubious practice (1999, pp. 201-4). Use of solitary confinement in remand prisons can damage the health of citizens who have not been condemned and are still until the sentence is pronounced-to be considered not guilty.

When one is studying the relationship between time spent in solitary confinement and health effects, negative (sometimes severe) health effects can occur after only a few days of solitary confinement. The health risk appears to rise for each additional day. Our knowledge is much more tentative concerning what happens upon release from solitary confinement. Several studies suggest that most negative effects wear off relatively quickly.

Other studies identify more or less chronic health effects. Most studies do not address the question of post-isolation effects, and more research is clearly needed. Still, a number of studies describe how formerly isolated inmates experience significant problems clearly related to their isolation experience – such as difficulties handling social situations and close social and emotional contacts. The only large-scale follow-up study identified less post-imprisonment “psychological compensation” among formerly isolated prisoners than among formerly no isolated prisoners.

A. Policy Implications

Solitary confinement harms prisoners who were not mentally ill on admission to prison and worsens the mental health of those who were. The use of solitary confinement in prisons should be kept at a minimum. In some prison systems, there is a clear and significant overuse. This is especially apparent in the case of the U.S. Supermax prisons. But the use of solitary confinement is problematic elsewhere.

While things have improved in Scandinavia in recent years, it is difficult to justify a practice of subjecting pre-trial detainees to solitary confinement to avoid a collision, when other Western nations can do without such measures or use this kind of solitary confinement much less. The basic advice must be to avoid using solitary confinement in order to protect ongoing investigations. The police must be able to instigate control measures in order to avoid detainee collusion, but twenty-two to twenty-four hours of isolation should be avoided. Isolation is simply “not good practice” (Coyle 2002, p. 73).

Books

Some books are mainly taken from the list of Peter Scharff Smith (see note below)

Preventing Torture: A Study of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

By Malcolm D Evans and Rod Morgan 1998. Oxford: Clarendon

Isolation – en plet på det danske retssystem

Retspolitiske udfordringer, by Ida Kock, Bent Sørensen, Manfred Petersen, Jørgen Warsaae Rasmussen and Henning Glahn 2003, Copenhagen: Gads Forlag

Om isolation i varetægtarrest “Vidnesbyrd om de psykiske og social følger af dansk isolationsfangsling” by Jorge Monzano 1980 and edited by Jørgen Jensen, Finn Jørgensen and Jørgen Rasmussen.

Haarby: Forlaget i Haarby

Note: I should like to provide a more comprehensive and detailed list later as to references and books, the subject is still most distressing for me to go into, moreover to read books as to solitary confinement.

Advocate Folmer Reindel told the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, in front of full Court of 17 judges from 17 member countries – 26th September 1988:

“It is clear that the Danish authorities had, for a long time, the objective to close down Hauschildt’s successful and profitable business, irrespective that the companies acted correctly and within the Danish law.

From the first day of the action against Hauschildt and his companies, it has been the objective of the Danish authorities to justify their illegal acts at any cost, including keeping Hauschildt in solitary confinement and pre-trial detention for more than four years as a hostage to justice.

The Danish authorities acted within total contempt for the Danish law and justice and the European Human Rights Convention.

Hauschildt and his companies became victims of the Danish State”

The west wing of Vestre Prison in Copenhagen, a place I spent years on pre-trial remand. My total solitary confinement was in another wing

Solitary Confinement: Punished for Life

The headline of an article in The New York Times,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/04/health/solitary-confinement-mental-illness.html

On Aug. 3, 2015

The following is taken from Department of Applied Psychology, New York State University, by Mary Murphy Corcoran

Copyright © 2018 by New York University

Effects of Solitary Confinement on the Well Being of Prison Inmates

Psychological Effects of Solitary Confinement

Confined inmates experience a multitude of psychological effects, including emotional, cognitive, and psychosis-related symptoms (Smith, 2006; Shalev, 2008). Solitary confinement is considered harmful to the mental health of inmates because it restricts meaningful social contact, a psychological stimulus that humans need in order to remain healthy and functioning (Smith, 2006). Longer stays in solitary confinement are associated with greater mental health symptoms that have serious emotional and behavioural consequences. (Smith, 2006; Shalev, 2008).

Emotional and behavioural effects of solitary confinement.

The majority of those held in solitary confinement experience adverse emotional effects that can range from acute to chronic, depending on the individual and the length of stay in isolation (Shalev, 2008). Confined prisoners also report feelings of panic and rage, including irritability, hostility, and poor impulse control. Additionally, they frequently exhibit symptoms of anxiety that vary from low levels of stress to severe panic attacks. Isolated inmates also experience symptoms of depression, such as hopelessness, mood swings, and withdrawal. These depressive symptoms may even escalate to thoughts of self-harm and suicide. As compared to the general prison population, rates of suicide and self-harm, such as cutting and banging one’s head against the cell wall, are particularly high in prisoners assigned to solitary confinement (Haney, 2003; Shalev, 2008; Greist, 2012).

Many of the issues that confined prisoners have during isolation are also prevalent post-isolation. Those who are isolated also exhibit maladjustment disorders and problems with aggression, both during confinement and afterwards (Briggs et al., 2003). Furthermore, inmates often have difficulty adjusting to social contact post-isolation and may engage in increased prison misconduct and express hostility towards correctional officers. (Weir, 2012; Dingfelder, 2012; Constanzo, Martinez, Klebe, Torrence & Livengood, 2012). While cases in which inmates have exhibited positive behavioural change after isolation have been documented, such a result is rare (Smith, 2006).

Cognitive effects of solitary confinement.

In addition to having disruptions in their emotional processes, inmates’ cognitive processes tend to deteriorate while they are in isolation. Some confined inmates report memory loss, and a significant portion of isolated inmates report impaired concentration (Smith, 2006; Shalev, 2008). Many are unable to read or watch television since these activities are their few sources of entertainment. Confined inmates also report feeling extremely confused and disoriented in time and space (Haney, 2003; Shalev, 2008).

Psychosis-related effects of solitary confinement.

Another confinement related psychological symptom that inmates may experience is disrupted thinking, defined as an inability to maintain a coherent flow of thoughts. This disrupted thinking can result in symptoms of psychosis (Haney, 2003; Shalev, 2008). Inmates who exhibit these symptoms of psychosis often report experiencing hallucinations, illusions, and intense paranoia, such as a persistent belief that they are being persecuted (Shalev, 2008). In extreme cases, inmates have become paranoid to the point that they exhibit full-blown psychosis that requires hospitalization (Smith, 2006).

The aforementioned mental health difficulties are not anomalies. Confined inmates often describe feelings of extreme mental duress after only a couple of days in solitary confinement (Haney, 2003; Smith, 2006). Some researchers have even compared confined inmates to victims of torture or trauma because many of the acute effects produced by solitary confinement mimic the symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. It is unclear how long these symptoms persist after release from solitary, but they are at least prevalent during and immediately after solitary confinement for most inmates (Haney, 2003).

Conclusion

The existing literature demonstrates that solitary confinement has both significant physiological effects, such as gastrointestinal upset and hypertension and psychological effects, including psychosis and depression (Shalev, 2008).

These findings suggest that the physiological and psychological consequences of solitary confinement are extremely dangerous to the well being of inmates. However, research regarding psychological effects is limited by the fact that many inmates are mentally ill prior to incarceration, making it difficult to distinguish whether psychological symptoms are directly produced by solitary confinement. Additionally, research is limited by the settings in which the studies must be conducted. Naturalistic studies conducted in actual prisons do not have control groups (Constanzo et al., 2012; Smith, 2006), while studies using contrived settings are also limited because they cannot fully mimic the harsh conditions of prisons due to the researchers’ ethical obligations. For example, the volunteers in studies using contrived settings are confined for much shorter periods of time compared to actual inmates (Bonta & Gendreau, 1990). Thus, these findings cannot be accurately compared to the real-life experiences of prisoners (Smith, 2006).

While these limitations must be considered, this research has serious implications for policy(Griest, 2012). Future evaluations of solitary confinement must be conducted to determine whether solitary confinement can be safely used in prisons or if it should be limited or eliminated (Griest, 2012). In addition, there is a definite need to find alternative incarceration methods to effectively manage the behaviours of inmates without causing harm to their physical and mental health. Developing new incarceration methods is particularly important to ensure the well-being of confined inmates who are mentally ill prior to incarceration (Bonta & Gendreau, 1990).

References

Bonta, J., & Gendreau, P. (1990). Reexamining the cruel and unusual punishment of prison life. Law and Human Behavior, 14(4), 347-372.

Briggs, C. S., Sundt, J. L., & Castellano, T. C. (2003). The effect of supermaximum security prisons on aggregate levels of institutional violence. Criminology, 41(4), 1341-1376.

Costanzo, M. L., Martinez, R. L., Klebe, K. J. Torrence, N. D., & Livengood, M. L. (2012, August). Predictors of placement into correctional solitary confinement. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Colorado Springs.

Dingfelder, S. (2012). Psychologist testifies about the dangers of solitary confinement. Monitor on Psychology, 43(9), 10.

Griest, S. E. (2012). The torture of solitary. The Wilson Quarterly, 36(2), 22-29.

Haney, C. (2003). Mental health issues in long-term solitary and supermax confinement. Crime & Delinquency, 49(1), 124-156.

O’Keefe, M. L. (2008). Administrative segregation from within: A corrections perspective. The Prison Journal, 88(1), 123-143.

Shalev, S. (2008). The health effects of solitary confinement. In Sourcebook on solitary confinement. Retrieved from http://solitaryconfinement.org

Smith, P. S. (2006). The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: A brief history and review of the literature. Crime and Justice, 34(1), 441-528.

Weir, K. (2012). Alone, in ‘the hole’: Psychologists probe the mental health effects of solitary confinement.

Copyright © 2018 by New York University | All rights reserved | NYU Steinhardt | Applied Psychology | 246 Greene Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003

In an interview with Life Science in 2015, Peter Scharff Smith from the Danish Institute for Human Rights in Copenhagen said:

“The effect of solitary confinement on a prisoner’s well-being is a subject that has been debated since the first half of the 20th century, according to Peter Scharff Smith, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for Human Rights in Copenhagen. While several studies have downplayed the negative effects of isolating prisoners for long periods of time, many more have concluded that this practice is quite harmful on both a physiological and psychological level, Scharff Smith told Live Science.

“When you look at all of the available research, it’s pretty clear that solitary confinement is dangerous. There’s clearly a risk of negative effects on health,” he said. Absolutely Evil Medical Experiments

Though the specific conditions of solitary confinement differ from one institution to the next, most prisons use “solitary” as a form of disciplinary punishment or to help keep order, according to Scharff Smith, who wrote an extensive review of studies on the effects of this imprisonment practice for the journal Crime and Justice in 2006.

“What these studies show if you look at them together, is that the main issue or problem [with solitary confinement] is the lack of psychologically meaningful social contact,” Scharff Smith said. Prisoners in solitary are usually kept in a small, locked cell for 23 hours a day and have very few interactions with other human beings (apart from the guards who escort them outside their cells for exercise or showers) he added.

This lack of social stimulation is linked to a slew of side effects that researchers have observed in prisoners who have spent time in solitary confinement. Some of the reported symptoms include anger, hatred, bitterness, boredom, stress, loss of a sense of reality, suicidal thoughts, trouble sleeping, confusion, trouble concentrating, depression and hallucinations.

Why does a lack of social interaction lead to so many negative side effects? One theory, posed by Huda Akil, a neuroscientist at the University of Michigan, is that the brain actually needs positive human interactions to stay healthy. Social interaction may activate growth factors in the brain, helping brain cells regrow, Akil said at a 2014 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Further, the problems that solitary confinement cause are not purely psychological. Studies have also linked this form of isolation to more physical symptoms, including chronic headaches, heart palpitations, oversensitivity to light and noise stimuli, muscle pain, weight loss, digestive problems, dizziness and loss of appetite.”

SOLITARY WATCH

https://solitarywatch.org/2014/08/04/what-solitary-confinement-does-to-the-human-brain/

What Solitary Confinement Does to the Human Brain

By Maclyn Willigan

August 4, 2014

Based on the evidence amassed by researchers in the last several decades, we have reached a point in time when we may unequivocally state that solitary confinement inflicts psychological damage and distress on those subjected to it. Even in individuals with no prior history of mental illness or instability, extended periods of isolated confinement have produced severe psychological symptoms, and left deep and often permanent psychological scars.

More recently, such findings have been bolstered by the field of neuroscience, which is progressively discovering evidence that long-term isolation has the potential to actually alter the chemistry and structure of the brain.

Among the early researchers investigating the link between solitary confinement and mental abnormalities is Stuart Grassian, who became interested in the subject after visiting Walpole State Penitentiary in 1982 and interviewing several men in solitary confinement. Grassian realized “these people were very sick.” Those he spoke with exhibited symptoms such as hallucinatory tendencies, paranoia, and delirium—a collection of conditions he designated “SHU Syndrome.” Several other studies have since supported the existence of such a syndrome. The American Friends Service Committee, among others, also cites hypersensitivity to noise and touch, insomnia, PTSD, and uncontrollable feelings of rage or fear.

The rise of supermaxes and solitary confinement units across the country in the 1990s and early 2000s has intensified the problems associated with prison isolation.

According to an American Journal of Public Health study, 53.3 per cent of self-harm incidents took place among those in solitary, who make up only about 5 per cent of the prison population. Likewise, about half of all prison suicides take place in solitary confinement. When their sentences are complete, individuals housed in solitary are often released directly to the streets—a practice that has been linked to increased recidivism rates.

Only recently, however, have researchers begun discussing the neurobiological effects of prolonged isolation. This research was showcased earlier this year at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), at a panel discussion during which neurologists and activists alike shared their experiences with solitary confinement’s destructive capabilities.

About HELL IS A VERY SMALL PLACE:

Hell Is a Very Small Place: Voices from Solitary Confinement

Now available as a paperback, hardcover, or e-book: https://solitarywatch.org/new-book-hell-is-a-very-small-place-voices-from-solitary-confinement/

President Barack Obama, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, and Pope Francis have all criticized the widespread use of solitary confinement in prisons and jails. UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan E. Méndez has denounced the use of solitary beyond fifteen days as a form of cruel and degrading treatment that often rises to the level of torture. Yet the United States holds more than eighty thousand people in isolation on any given day.

In a book that will add a startling new dimension to the debates around human rights and prison reform, 16 men and women currently and formerly former imprisoned in solitary confinement describe its devastating effects on their minds and bodies, as well as the solidarity expressed between individuals who live side by side for years without ever meeting one another face to face, the ever-present specters of madness and suicide, and the struggle to maintain hope and humanity in the face of crippling isolation and deprivation.

These firsthand accounts are supplemented by the writing of noted experts, exploring the psychological, legal, ethical, and political dimensions of solitary confinement. Solitary Watch’s James Ridgeway and Jean Casella provide a comprehensive introduction, and Sarah Shourd, herself a survivor of more than a year of solitary confinement, writes eloquently in a preface about an experience that changed her life. The powerful cover art is by renowned political artist Molly Crabapple.

History of Solitary Confinement Is Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Individuals Recently Released from Prison

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11524-017-01 ABSTRACT

Abstract

This study assessed the relationship between solitary confinement and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in a cohort of recently released former prisoners. The cross-sectional design utilized baseline data from the Transitions Clinic Network, a multi-site prospective longitudinal cohort study of post-incarceration medical care. Our main independent variable was self-reported solitary confinement during the participants’ most recent incarceration; the dependent variable was the presence of PTSD symptoms determined by primary care (PC)-PTSD screening when participants initiated primary care in the community. We used multivariable logistic regression to adjust for potential confounders, such as prior mental health conditions, age, and gender.

Among 119 participants, 43% had a history of solitary confinement and 28% screened positive for PTSD symptoms. Those who reported a history of solitary confinement were more likely to report PTSD symptoms than those without solitary confinement (43 vs. 16%, p < 0.01). In multivariable logistic regression, a history of solitary confinement (OR = 3.93, 95% CI 1.57–9.83) and chronic mental health conditions (OR = 4.04, 95% CI 1.52–10.68) were significantly associated with a positive PTSD screen after adjustment for the potential confounders. Experiencing solitary confinement was significantly associated with PTSD symptoms among individuals accessing primary care following release from prison. Larger studies should confirm these findings.

By Gali Katznelson and J. Wesley Boyd

Gali Katznelson is a Master of Bioethics candidate at Harvard Medical School and a fellow at the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology and Bio

Let’s call it for what it is: Placing prisoners in solitary confinement is tantamount to torture and it needs to stop.

The practice of placing incarcerated individuals in solitary confinement dates back to the 1820s in America when it was thought that isolating individuals in prison would help with their rehabilitation. Yet, over the past two centuries, it has become clear that locking people away for 22 to 24 hours a day is anything but rehabilitative. Solitary confinement is so egregious a punishment that in 2011, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment condemned its use, except in exceptional circumstances and for as short a time as possible, and banned the practice completely for people with mental illnesses and for juveniles.

Despite its barbarity, the United States continues to place thousands of people, including individuals with mental illnesses and children, in solitary confinement, sometimes for decades. Thirty years ago, Dr. Stuart Grassian, who recently spoke at Harvard Medical School’s “Behind Bars: Ethics and Human Rights in U.S. Prisons” conference, evaluated 14 individuals placed in solitary confinement and found the same symptoms in many of them:

hypersensitivity to external stimuli; perceptual disturbances, hallucinations, and derealisation experiences; affective disturbances, such as anxiety and panic attacks; difficulties with thinking, memory and concentration; the emergence of fantasies such as of revenge and torture of the guards; paranoia; problems with impulse control; and a rapid decrease in symptoms immediately following release from isolation.

Taken together, Dr. Grassian proposed that these symptoms amount to a pathopsychological syndrome.

Since his initial work, ample medical literature has corroborated these findings. Social psychologist Dr Craig Haney interviewed people in Pelican Bay State prison and told the New York Times that 63 percent of men kept in solitary confinement for 10 to 28 years said they consistently felt on the verge of an “impending breakdown,” compared to 4 percent of individuals in maximum-security prisons. He reported that 73 percent of people in solitary confinement felt chronically depressed, compared to 48 percent of those in maximum-security settings.

The psychological effects of isolation last long after individuals are removed from isolation. Indeed, years after their release, many who experienced solitary confinement in Pelican Bay had difficulty integrating into society, felt emotionally numb, experienced anxiety and depression, and preferred to remain in confined spaces.

Solitary confinement often exacerbates existing psychiatric conditions and not infrequently leads to suicide. In Texas, for example, suicides rates for those in solitary confinement are five times higher than that of the general prison community. Given that the U.S. has 10 times as many people with mental illnesses in jails than in state hospitals, the use of isolation for people with mental illnesses is beyond troubling.

Mental health issues are also widely prevalent in youth within correctional facilities, and placing youth in solitary, often as a form of punishment or simply because prisons are understaffed to engage with these children, is psychologically damaging and outright cruel. Dr. Louis J. Kraus, a child, adolescent and forensic psychiatrist, also spoke at the Harvard conference, and explained that locking children up in isolation worsens their mood symptoms, worsens trauma-based pathology, increases anxiety symptoms, compromises these children’s trust, and increases the risk of suicide.

The upshot is that continuing to place these individuals in solitary confinement is both inhumane and unethical. Multiple organizations agree, including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Medical Association and the United Nations. Nonetheless, thousands of children continue to be placed in solitary confinement across the U.S.

The verdict is clear: Solitary confinement causes such severe psychological damage that it is tantamount to torture. Prison systems in other countries such as Germany and the Netherlands have found ways to function effectively while greatly restricting its use. We can too. The United States needs to be more humane to the more than two million of its people that are in the U.S. corrective system, and the first step toward doing so is straightforward: stop engaging in torture via solitary confinement.

Gali Katznelson is a Master of Bioethics candidate at Harvard Medical School and a fellow at the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology and Bioethics at Harvard Law School.

In the last 40 years since my solitary confinement so much research has been done, the effects are known to us. Here is some website to visit:

http://solitaryconfinement.org/uploads/sourcebook_02.pdf

http://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2018/01/17/solitary-confinement-torture-pure-and-simple/dden-damage-solitary-confinement

https://www.newsweek.com/2017/04/28/solitary-confinement-prisoners-behave-badly-screws-brains-585541.html

https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/solitary-confinement-mental-health-0625125

https://www.livescience.com/51212-solitary-confinement-health-effects.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/04/health/solitary-confinement-mental-illness.html

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/what-does-solitary-confinement-do-to-your-mind/

http://sfbayview.com/2018/02/ptsd-sc-post-traumatic-stress-disorder-solitary-confinement/

https://www.therichest.com/shocking/15-chilling-facts-ab

https://brandongaille.com/23-shocking-solitary-confinement-statistics/

https://io9.gizmodo.com/why-solitary-confinement-is-the-worst-kind-of-psycholog-1598543595

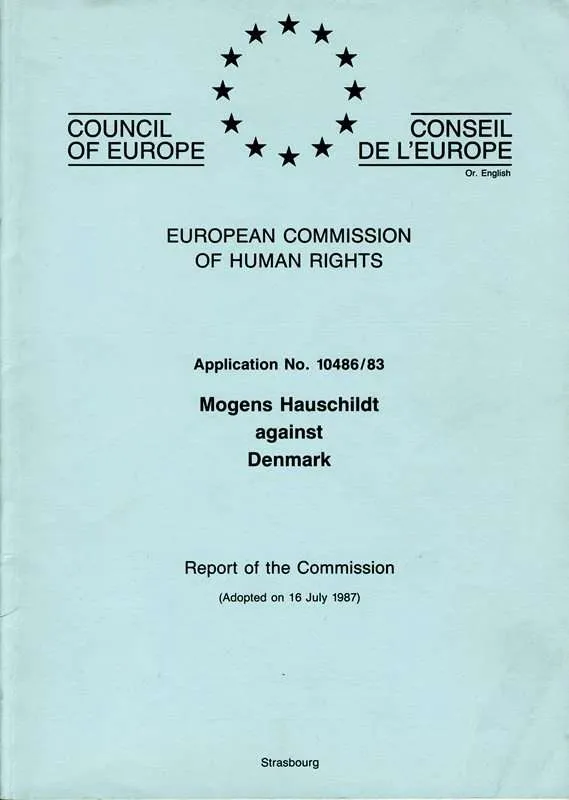

HAUSCHILDT v. DENMARK

The European Commission and the Court of Human Rights Judgement, Comments and Reports 1982-89

PLEASE NOTE!

This website is continuously hacked – for some reason? The facts and truth are not appreciated; I apologise that some pages are faulty as to their layout at times.

This was my solitary confinement cell, and later the kind of cell I remained in during my 1492 days pre-trial incarceration - just this cell is newly painted and with better lights and stone floor

Report to the Commission July 1987

JUSTITSLIG

Although that I have shaken hands and been in the company of kings, queens, presidents, prime ministers, princes and princesses, Nobel price laureates, ambassadors and captains of finance and industry, during the last 42 years I never found myself again after the terrible events in Denmark, I am not who I was, I have lived as a changed person marked by the scars which the Danish State inflicted on my family and me.

I did leave my isolation cell, but the solitary isolation has never left me!

JEG EFTERLYSER

Jeg søger personer som kan bidrage med oplysninger, fakta og dokumentation omkring Dansk total isolation tortur under varetægtsfængsling. Enhver som har været udsat for denne tortur længre end lovligt og stadigvæk bære sårene. Kontakt: Info@justitslig.com