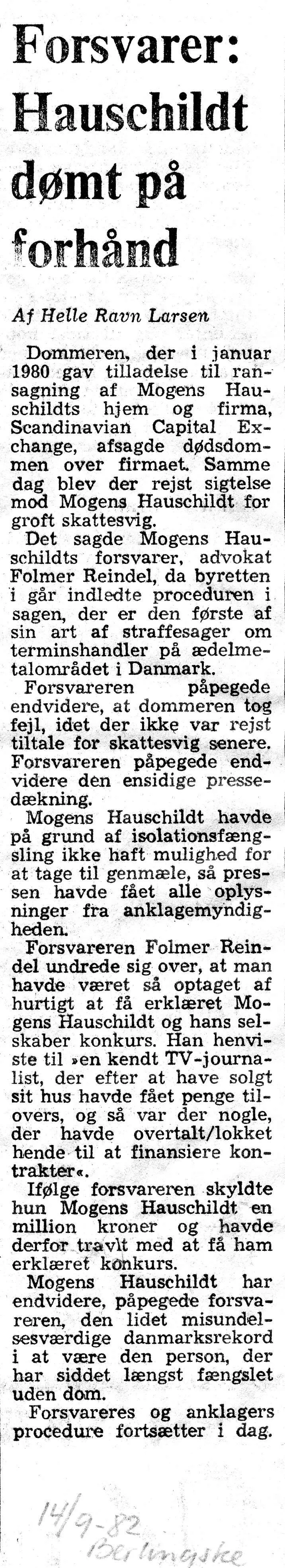

The High Court Judge Brink’s Clear Misconduct

On the 2nd August 1983, I wrote a letter to the President of the High Court making references to the letter from Judge Brink to me (dated the 26th May 1983), as to various complaints I had made including the alleged misconduct by Judge Ove Brink, the head of my trial.

The President of the High Court replied to me on the 10th August, setting out the statement by Judge Brink, who reserved his right to not answer the charges.

At the opening of the trial in the High Court on the 15th August, my defence and I stated the objections with regards to Judge Brink’s clear misconduct as well as to Judge Reisz who had already made one of the most important decisions against me in the lower court.

Judge Reisz made four days after my arrest and solitary confinement an order to seize all my assets – at that time neither myself nor the companies were made bankrupt. Moreover, there was no evidence as to my alleged tax evasion or fraud.

Where was the presumption of innocence? It appears in every human rights treaty and in Rule 21 of the Hague Tribunal and as Article 66 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Judge Reisz decision caused the “excuse” for the bankruptcies and at the very least justified that the authorities could, despite the true solvent position of the companies and me, go and make the companies and I bankrupt.

The other judiciary, Judge Brydensholt, had also made ten decisions through the years of my pre-trial incarceration against me dating back to 1981. I had, however, somewhat greater respect for him – although it perhaps would have been right and correct to claim that all three judges were clearly biased as they all had all made decisions against me and kept me in pre-trial incarceration as well as solitary confinement. Nevertheless, I did not object to Judge Brydensholt serving at the time as one of the judicial judges.

After some discussion, my defence and I agreed to let Judge Reisz remain as a judge but not to let Judge Brink remain since there were many witnesses to his misconduct and prejudicial behaviour towards me. After all, thirty-five judges in the High Court had, through the years, decided against me and so there were very few judges left who had not been involved before with me and my case and had consequently somewhat committed themselves.

After nearly forty minutes of voting, the three judiciary judges, with Judge Brink residing as head, decided that he should remain in charge of the trial. Interesting – this voting did not include the lay-judges, which appeared to be against the decision before the case started at the High Court.

When judge Brink told the court of the decision made, he said that I could appeal directly to the Supreme Court without the Ministry of Justices’ permission. That was a direct lie and he knew it, but the defence and I did not at the time.

The way that this whole question has been handled by the authorities – where Judge Brink himself is responsible for the appeal that never goes to the Supreme Court and where Judge Brink never answers to the alleged charges of misconduct – can only be viewed with considerable scepticism.

Judge Brink, as the head of the Court, conducted the examination of witnesses and did on many occasions show considerable bias and even nearly adorned the robe of the prosecutor. Furthermore, judge Brink did make some very curious and controversial decisions which also must have been a violation of the principle of a fair trial.

In light of the Judgement of the European Court of Human Rights later, and the resulting changes in Denmark, it is blatantly clear that Judge Brink and in fact the other judges should not have taken part in the High Court proceedings. Specific as it was not a really a proper appeal trial, but a rubber-stamp of the lower court’s decision. How could they be objective and seen to be fair, after making so many decision against me?

Most judges in Denmark, at the time, did not have the backbone to stand up to governments and power-wielders in the society. It was clear in my case that all the prior decision in the case from which bias as to it outcome might reasonably be apprehended. There was simply, in Denmark, at the time no safeguard as to the judges’ independence and impartiality.

At the time, 34 High Court judges had made decisions and judgement against me and my defence, how could any of these judges be objective and impartial, when they already had shown their sympathy and prejudice against me. They had already applied preconceived biases about my person and the case.

Judges Independence and Impartiality

Judges Impartiality is the ability of a judge to render an equitable and just decision based upon the law and/or equitable principles. An impartial judge is unbiased and does not have a prejudice against or give sympathy to either side of legal action.

Further, judicial independence is the concept that the judiciary should be independent of the other branches of government. That is, courts should not be subject to improper influence from the other branches of government or from private or partisan interests. Judicial independence is important to the idea of separation of powers.

There was no judicial independence in Denmark, as the Ministry of Justices controlled the Police, Prosecution, the appointment of judges and the Prison Service. All the judges appointed to the High Court had worked all their lives to put people behind bars and make guilty judgments. They had loyalty and an obligation as a colleague to follow the line.

https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/training9chapter4en.pdf

It is well settled that impartiality is determined according to two tests, subjective and objective. The European Court of Human Rights held that,

“…the existence of impartiality for the purpose of Article 6-1 must be determined according to a subjective test, that is on the basis of the personal conviction of the judge in a given case, and also according to an objective test, that is ascertaining whether the judge offered guarantees sufficient to exclude any legitimate doubt in this respect”.10

On the objective test, the European Court of Human Rights observed,

“Under the objective test, it must be determined whether, quite apart from the judge’s personal conduct, there are ascertainable facts which may raise doubts as to his impartiality. In this respect even appearances may be of a certain importance. What is at stake is the confidence which the courts in a democratic society must inspire in the public.”

Impartiality and the appointment of Judges

One of the key components of impartiality and independence in the manner of the appointment of Judges. Reference is made to a pronouncement of the European Court of Human Rights on its interpretation of Article 6.1 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Article 6.1 was drafted in almost similar terms as Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

“In determining whether a body can be considered independent the Court has had regard to the manner of appointment of its members and the duration of their term of office and the question whether the body presents an appearance of independence”

It was impossible to consider the independence of judges at the time in Denmark. The Ministry of Justice operated a “protected and cosy little shop” and practically no one could fall out of line.

Judicial independence is a cornerstone of our system of government in a democratic society and a safeguard of the freedom and rights of the citizen under the rule of law. The Justices must take care that their conduct, official or private, does not undermine their institutional or individual independence or the public appearance of independence. No such qualm in Denmark at the time.

Judge Brink’s Death in the High Court

At mid-day on the 7th December 1983, Judge Brink certainly stood up, from his chair, during the proceedings and collapsed from a heart attack and consequently died. Just prior to this, my defence had made some serious argumentation with regards to the trial not being fair and unbiased. They had strongly criticised the proceedings in general, as well as the made-up transcripts from the Court, entirely based on the manufactured and biased dictation by transcripts by judge Claus Larsen in the Lower Court.

There is no doubt that there was a lot of pressure on Judge Brink; perhaps he had some moral doubts – who know. But he died at the relatively young age of sixty-three whilst carrying out his duty as a henchman of injustice for the Danish authorities in my case.

A little note to this, when judge Brink fell over, I did utter to my two defence lawyers (Folmer Reindel and John Korsø-Jensen) – I am sure he is dead, even said, that I hoped he died. I did get an immediate negative reaction to this statement from Korsø-Jensen, but Korsø did not carry my scars or hate at the time.

The 7th of December have through my life meant a lot to me, firstly, it was my dear grandmother’s birthday, she had died already in 1950, later the date becomes a kind of celebration as it was Pearl Harbour Remembrance Day and the date I chose for our annual Christmas party in Mayfair, the venue held on rotation at the various hotels (The Claridges, The Dorchester, The Four Season, The Mayfair, Grosvenor House and the InterContinental.)

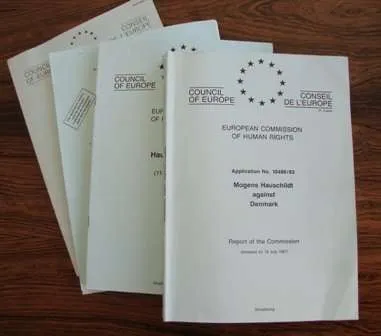

HAUSCHILDT v. DENMARK

The European Commission and the Court of Human Rights Judgement, Comments and Reports 1982-89