The Danish Population Was all Fooled by the Danish Authorities

When the Danish media reported of millions of losses, they did not refer to my losses, or the companies losses as a result of my arrest and the Danish authorities’ action on the 31st January 1980 closing the companies. An act which entirely had political motives, apart from the trumped-up charge against me for “serious” tax evasion which had no foundation.

The Danish population was all fooled by the Danish authorities wish to cover up everything. The Government had succeeded in selling Bagmandspolitiet’s role and indeed found someone to be the lamb leads to slaughter.

Yes, the Danish population was fooled. When I on the 18th January 1980 received confirmation that the market was going to crash, I immediately ordered the transfer from Switzerland to London of nearly US$2 million to enter the market on the “short” side using the London Metal Exchange.

I made detailed plans to sell more than 40 contracts “going short” on any rebound of the silver price. Prices do not just fall or go up, they regularly have a “technical reaction” to these moves and consolidate their moves before moving on. When this happened, I was ready to sell into the market. I spend many hours every day studying the price movement and made various technical charts apart from the charts which had been made by my staff. I was initially involved in the late 1960s with what become later the Society of Technical Analysis (STA). I had, therefore, considerable experience as to the technical analysis of price movements.

We did not have any technology to produce these charts just in front of us. It took many working hours every day to draw the various chart for various commodities and currencies. As a chartist, I could trace all the various technical reactions and where I would enter the market.

As I expected, the precious metal price came off in the Far East following the US exchanges announcement on Friday (18th January). The gold and silver prices were marked down early in Europe in line with Hong Kong. Friday gold had traded at over US$ 740 a troy ounce and silver had reached nearly US$ 56 an ounce for March deliveries and $50 for cash. On the Monday and Tuesday, both metals were marked down, gold dropping to $590 at Tuesday’s close and silver swinging between $43 and $34 on the day.

SCE’s A/S average sale price on all the margin sales was above the equivalent to US$38, so we were making good money all the way down. Nevertheless, I wanted to take advantage of this “one in a lifetime opportunity” to make an additional US$50-100 million by selling into the market, on a sure trade. Therefore, I transferred the US$ 2 million to London from Switzerland. At the time of my arrest, this money was on 2 days call, which meant that I could get this money to the exchange at any time.

As I have reported other place on these web pages, I considered the crash in prices as a certainty, not a question of a hunch or speculation, no absolute certainty, as I looked at it.

Why, when only sellers can enter the market and liquidate contracts, the price will fall for sure. This applies for all kind of trading, not just the precious metals. With no buyers around prices will fall, sooner or later.

To go long in the market would cost a fortune because of the deposit requirements by the exchanges. So, in fact, to buy and go long was for all purposes not possible, when you understand the market.

Just prior to Christmas I took profit in all the precious metal contracts which I was long, considering the market. Most professional view the market as somewhat overheated and expected a technical reaction downwards. Even the highly respected Green’s (Greens Commodity Market Report 19 December 1979) advised everyone to sell. They even predicted what I also was convinced of, that Comex would sooner or later make a ruling as to all the short position in the market, something which happened on the 17th January nearly a month later. In fact, quoting from Green’s as to their view on silver: ”The previously heralded squeeze in December did not materialize, but we are convinced that those short February delivery in Chicago and the March delivery on Comex will have great difficulty to extricate themselves from their positions. Probably the only salvation for the shorts lies in some kind of ruling by the Board of Governors of both exchanges forcing liquidation at a fixed price. (The Comex by-laws provide for such eventuality.)”

Now when most of these Governors are professional floor traders – all short thousands of contracts, they will first and foremost protect themselves, everyone knows the market should know that. No one should go long in the market with such a situation. Therefore, I did not buy silver from that time onwards since it would, in my opinion, be stupid.

One cannot speak of silver futures contract trading history without citing the abrupt rule rigging which occurred in mid-January 1980 when the Hunt Brothers supposedly cornered the silver market. Somehow these trust-fund silver price ‘gamblers’ forgot who owned the casino and ultimately exactly where the interests of those who allowed it to exist in the first place were.

OK, Afghanistan came over Christmas with the invasion by the Russians, but I still accessed the market on the short side. However, it was difficult seeing the prices moving against me until the 17th of January.

The good thing, most financial commentators, did not have much knowledge about how the markets work back then. Even respected journalists still were recommending going long “buying” in the market and to my joy at the time; even the Danish financial press was full of “buy stories”. Even Financial Times was bullish on gold (see: Financial Times 24th Jan 1980 ).

When journalists reached me for comments, I always made sure to refer to others views of the market, not my views, as I did not want to be caught advising the public to buy, well knowing that the prices would crash. Moreover, I pointed out that anything could happen as to Afghanistan and in Iran; moreover, people should always buy gold for insurance against what may happen in the world. Even after my arrest and any professional would know that the market was crashing, Danish newspapers recommended buying gold. In fact, a major Danish magazine BilledBladet published on the day of my arrest an article about my companies (see: Det stiger og stiger ) Interestingly, when the journalist came to make this article, I did not want to appear, because, I was convinced the market would crash, however, others in the company still believed in other so-called experts.

Now, some people reading these lines may think, he was a greedy bastard – yes, but I only wanted to make up for all the bad months in late 1979 where I had accepted losses, at least on paper. Some people will also criticize me morally, why I did not instruct my staff to call all our clients and tell them to liquidate their contracts as prices would fall. Such critic should see the film Margin Call, an entangling thriller involving the key players at an investment firm during one perilous 24-hour period in the early stages of the 2008 financial crisis. To me, it truly reflects the mentality of Wall Street, and indeed it shows what happened when an investment bank is left with bad assets on its book. Many investment banks, including Goldman Sachs, sold the worthless paper to their clients.

Well, all our client had by their own free will went into their trades with the companies. We may have had some good salespeople, but people contacted us, and we did not put a gun to their heads. We did not like any licenced bank, or financial institution have an obligation to give our best and objective advice. As we have seen in the last years, banking is all about making money with other peoples.

Yes, I did what many successful business people have done, exploit the situation to maximum gains. For several months the year earlier, I had to daily see the market working “against me”, and now I found myself at the top of the mountain and could only get a good ride down. What I did not know Bagmandspolitiet was listening in to all my telephone call, where I stated that I was sure that all the prices would crash, making the companies and me a little fortune.

As my defence explained to the courts through the years, the serious tax allegation was entirely a drum-up allegation; we never did find out “what these charges entailed as I was never charged with tax evasion”.

In the days just following my arrest, the companies could still have been saved, by allowing me the freedom to transfer funds from abroad. What more, legally claim that the Danish authorities had sparked a paragraph in our business terms and condition, which more or less was a so-called “Force Majeure Clause”. This paragraph set out clearly that the companies would not be responsible for any actions by the government; we did have at the time concern that the Danish government could stop currency transaction if the international situation deteriorated; also, we did have a long experience how the National Bank had been trying to pull the chair away from under us.

Bagmandspolitiet knew I was “confident” of this clause in our standard business terms and conditions since in the days before my arrest I spoke to a lawyer on the telephone as to this specific clause including actions by other governments. Not that I expected anything as to Denmark but the world was in upheaval at the time with the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, the start of the Iran/Iraq conflict and so many other headlines which could affect deliveries and trading of commodities.

Bagmandspolitiet also knew from listening to the telephone conversation that we expected to make margin calls for millions at the end of the month (31st January). They had to act, otherwise later they had no chance to stop the companies and indeed me.

The most client who had been buying since December had lost considerable amounts as of the end of January; this required us to call for more money or liquidations of their contracts. The margin call would also have provided the companies with even more liquidity and profits from the liquidation of contracts as a result of the non-fulfilment of payments.

All this was never to be – I was arrested and the companies closed without any reference to Law and Justice.

A large number of clients in the companies was also fooled by the Danish authorities because they missed out on DKr. 14-18 million-plus which I offered a few days after my arrest to bring to Denmark. This money remained out of reach by the Danish authorities. The Danish authorities wanted to close down our business at all costs with total contempt to the laws and make me “example”.

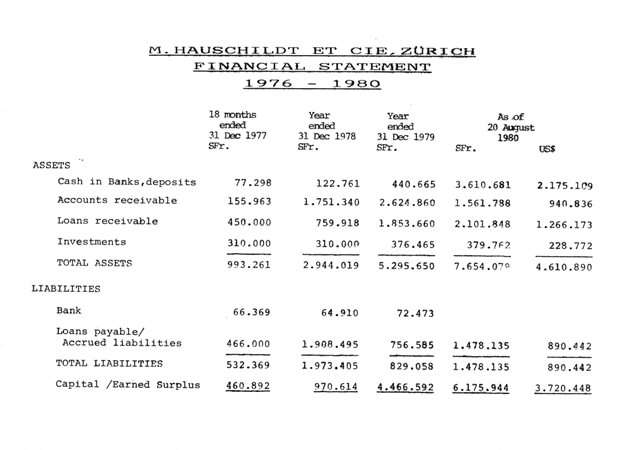

M. Hauschildt et Cie Zurich

The company had been trading for more than six years at the time of the event in Denmark. Prior to moving to Denmark, I had established this “unlimited liability” company specifically with the intention that the company, after trading 10 years would “more or less” get a bank licence in Zurich. Such a banking license alone was worth considerable goodwill value at the time, at least Sw.Fr. 10 million just to have the licence. It was a known fact that if you traded with unlimited liability for ten years, you could expect to get a banking license. My partner in M. Hauschildt et Cie was Bryan Jeeves, the Honorary British Consul in Liechtenstein. See Brian Jeeves, CMG OBE

Due to what had happened to me in Denmark, Bryan Jeeves went on and established what is today The Jeeves Group with offices around the world. The company is family-owned, and the controlled group is offering independent trustee, fiduciary and corporate services to private and corporate clients. The Jeeves Group also acts as a multi-family office for high net worth individuals. All such services were planned by M. Hauschildt et Cie, something, which I already had attempted with Associated Financial Planning in London in 1969, together with the Duke of St.Albans, Marquees of Reading, James Talbot and Euan Inchball.

M. Hauschildt et Cie traded with unlimited liability and I like its leading partner responsible with all my assets for all the company’s dealing. This structure had been used for hundreds of years by the Merchant banks and Swiss private banks.

Just prior to the events in Denmark, I had for some time been negotiating to bring in some more partners to M. Hauschildt et Cie. On a visit to New York in 1979; I had found an American banker who wanted to join us in Europe. In addition, I had found a Swiss financial advisor who was working for one of the banks we worked within Switzerland. These two people I had several meetings with during January in Zurich, latest four days before my arrest.

We had been finalising the arrangement and plans for a private banking “boutique” in Zurich. One of the people was to bring considerable investment banking experience to the company working for a respected Swiss bank and the other a substantial amount of client from all over the world. Both people represented valuable resources for the company bringing tangible assets and development. Due to the events in Denmark, this did not transpire, and everything was lost as to this important development.

As a result of the events in Denmark with my arrest, and the fact that my wife did not go to Switzerland (she had all the power of attorneys), my lawyers had to enact protection of M. Hauschildt et Cie. Sadly this protection of the estate, something similar to a U.S. Chapter 11 protection, became a big problem creating huge losses. The appointment of trustees, who basically just put the money into their own accounts, charging regular fees in return for no work.

Worst the exchange of all liquid assets into Swiss Francs, at the most unfavourable time and rate. The deposits in London was earning up to 15% plus, more than US250,000 a year and after being exchanged to Swiss Francs earning no interest at all, or just less than 1%. Later the liquid assets were placed with Swiss Air, earning less than 0.5 % p.a. (without security), one of the trustees worked for Swiss Air, a company which was for years mismanaged and ultimately went bankrupt.

The various trustees and lawyers bleeding the assets of the company by charging hefty fees, despite there was nothing to do. The lawyers even started suing each other and charged for everything including and visits from the Danish liquidators and prosecution, allowing them to take millions through the years.

So when the Danish tabloid was writing that I was earning millions every year from my pre-trial restrictive incarceration, that was also a blatant lie, in fact, I was losing money all the time.

Interestingly, it was the former prosecutor for Zurich who helped me. Hans Ulrich Hardmeier fought for years trying to get the company out of the “protection” and the greedy hands of several lawyers and auditors. He had total contempt for the Danish estates and the Danish government after how Denmark treated me. Charging fees fighting each other, on my account.

Moreover, he had total contempt for the lawyers in Switzerland who took the opportunity to charge millions, in return for no work, as to the company under “protection”, something caused by the Danish liquidator’s greed. The lawyers only took advantage of the fact that Denmark held me for all those years.

Hans Ulrich Hardmeier was one of the few lawyers I have met in my life who I consider as a decent person; yes to be a lawyer and decent human being is possible. Most lawyers are leeches and opportunist on human society and their client. I used to tell a joke: What has a lawyer and a human sperm in common? One in a million chances to become a human being!

First in 1990 was M. Hauschildt et Cie out of this stranglehold, solvent and indeed able to resume business. However, in 1990 I had lost all my goodwill, my mental strength, having been locked up for 1492 days, branded a criminal by the Danish tabloid and finished in financial services forever. Nevertheless, M. Hauschildt et Cie was there and solvent as it had always been, like its unlimited partner me, except been raided for millions by the lawyers.

Less than two years later, in September 1992, my son Hans Christian and I helped my son Mark Anthony and Lars Seier Christensen to start Midas, which become Saxo Bank. We supplied the seed money to start what became a very successful bank. I had always seen the great opportunity in investment banking in Scandinavia, but I could not do anything, as my name had become criminalised by Bagmandspolitiet. Despite three of my sons worked in banking and finance in London City and abroad for years, only one of my sons Mogens Alexander has remained in finance in North America. My son Mark brought his friend, from Spain, Lars Seier to London, where they worked together for some years before they went to Copenhagen to a start-up business. My two lawyers from the trial, Folmer Reindel and John Korsø Jensen both became involved, first Folmer who took care of the legal side for years and later John Korsø Jensen for Saxo Bank and indeed Seier Capital.

Nevertheless, the little money left in Hauschildt et Cie kickstarted Saxo Bank. Even when I in the mid-1980s was offered to head the Society of Technical Analysts in London, an organisation I already attended in 1968-69, I had to decline, after helping to establish the society as a non-profit company in the late 1980s, today a highly respected City institution. They still use the logo I designed.

In the 1980s and 1990s as chairman of The Mayfair Society and The Mayfair Trust and head of the Residents’ Association of Mayfair, I was subject to blackmail, as to the event in Denmark. This ultimately meant that I had to step down, and later subject to a “payback” from powerful elements of the British establishment after I exposed the systemic corruption in local government, specific Westminster City Council with Lady Sherley Porter running to Israel. Denmark supplied the ammunition for an in absentia trial, without me, defence lawyer, defence witnesses and documentation (see “Postscript“).

“The Danish National Bank, the Ministry of Trade, the Company Register and Copenhagen tax authorities all conspired against Hauschildt and the companies while using the involvement of the Ministry of Justice, the Special Prosecution, the media and courts as henchmen.”

– Advocate Folmer Reindel to the City Court

How stupid as to all the above assumptions, even in Børsen newspaper, about M. Hauschildt et Cie. They could just go to the Company Register in Zurich and see that Bryan Jeeves and I was they only two partners in the company. UniCapital had nothing to do with M. Hauschildt et Ce. I owned 100% UniCapital SA in Liechtenstein and had done for close to ten years at the time. Bagmandspolitiet knew all this, as I had papers in my office as to this, everything was “an open book” as I did nothing wrong and as to these companies had nothing to hide.

It is interesting in the above newspaper article that Judge Claus Larsen refused to accept my new defence lawyers Folmer Reindel and Korsø-Jensen. The court and prosecution had a cosy set-up with Manfred Petersen, one of them and they thought they could control everything. Manfred Petersen was nothing like Jørgen Jacobsen and could never be, although, I respected some of his work, obviously, he had to serve his paymaster as all defence lawyers at the time.

It was first after the Danish Law Society had expressed concern and advised that I should have two defence lawyers, that Folmer Reindel and Korsø-Jensen was allowed to defend me.

I was chopped down

This tree (what is left of it), I passed for years on my daily walks in the great national park of Harz. It reminds me of what happened to me when I was chopped down by the Danish authorities at the prime of my life. I made the mistake to show too much, most of my roots could be seen and this made me vulnerable. To some extent, I was an open book. The lesson, do not show too many of your roots, hide some away otherwise you leave yourself vulnerable.

If the Danish authorities with their “Jantelov” prosecution, had not arrested me on the 31 January 1980, six weeks later I would possibly be worth more than $100 million. I was assured to make huge profits from my decision of following the people who make the rules on the financial market (the regulators), I was right; however, I ignored the rules set by the Socialist Danish Government and their Jantelov.

The Hunt brothers ignored both the changing rules of the investors game and the power of the authorities. At least they did not end up in total solitary confinement for 309 days!

The Hunt Brothers and their Attempt to Corner the Silver Market in 1979-1980

In the early seventies, amidst political upheaval, inflationary pressures and stagnant economic growth, the wealthiest family in America (at the time), the Hunt family of Texas, tried to corner the market on precious metals. As a way to hedge themselves from the rampart printing of dollars the US government was doing, the Hunts decided to accumulate large amounts of hard asset investments. Since gold could not be held by private citizens back then, the Hunt brothers focused on silver.

In 1979, the Hunt brothers, along with a group of wealthy Arabs, formed a pool buying silver and silver futures. The Hunt brothers used their positions in silver futures to acquire more of the physical metal. As cash was continually losing value due to inflation, the Hunts decided to settle their long silver futures contracts with the delivery of silver, instead of cash settlement. Before too long, they had amassed over 200 million ounces of silver which were about half of the world’s supply.

Prices soon started to appreciate. When they began, the price of silver was below $5 ounce. By late 1979/early 1980 prices had increased tenfold and were trading near $55/oz. During this rise in prices, the COMEX and Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) only had about 120 million ounces of silver between them. As prices went higher and new buyers got into the market, the exchanges became increasingly fearful of defaulting. As the Hunts owned 77% of the world’s silver, either in physical form or futures contracts, the market had been cornered.

Things began to change once Paul Volker was named Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Volker was determined to get inflation under control by raising interest rates. Couple that with changes in trading rules at the CBOT and COMEX in Mid-January, prices soon plummeted. Things had gotten so out of whack that COMEX only accepted liquidation orders, effectively halting silver from going higher and giving certainty to all traders who were short in silver, like Scandinavian Capital Exchange. The CBOT set limits on the amount of silver any one entity could hold and raised margins. Not surprisingly prices came down significantly quickly and were trading near $10 by the end of March 1980.

The precipitous drop in prices meant huge losses for many speculators and ultimately forced the Hunt brothers into bankruptcy. By the mid-80s, the Hunt brothers had more than a billion dollars in liabilities they could not meet. At their peak, the Hunt brothers had held over $4.5 billion in silver on their $1 billion investment. On March 25, 1980, the Hunt brothers couldn’t meet their $135 million margin call, forcing the Hunt brothers to ‘shut it down.’ In August of 1988, the Hunts were convicted of conspiring to manipulate the market.

It was in late March 1980 that we had “Silver Thursday”, a day where the price of silver went from roughly $20/oz to $10/oz, a loss of over 50%. Ultimately, the Hunts had to be bailed out by New York banks so they could make good on their obligations. Their obligations had grown so large that the government forced the banks to issue credit so that widespread failures could be prevented.

The Hunts had exposed themselves to huge amounts of leverage, which worked great in the beginning. It was this leverage from the futures markets that ultimately did them in. The Hunts ended up losing because they couldn’t fight the Fed and the system as a whole. The exchanges changed the rules once they saw they were outmanoeuvred and couldn’t default, which would have led to widespread failures. Not only that, but many of the regulators who helped change the rules were also short silver.

In the end, cornering the market is not only illegal but immoral as well. In a truly free market, cornering the market wouldn’t work as alternative investments would gain favour. Also, as supply is taken off the market, buying the last bit of any commodity would become prohibitively expensive. If the Hunts had only bought physical silver, there was nothing that the financial industry or the government could have done. Conversely, if they only bought physical silver, the market probably wouldn’t have gone up that much, but they would never have had any futures contracts obligations to meet.

Today, the price of silver is finally close to testing the artificial highs of the early 80s. Similar to the late 70s, inflation is spreading, political situations around the globe are precarious at best and energy prices are near highs. Position limits and daily marked to the market accounting makes it nearly impossible to corner any market today. In the end, the Hunts tried to fight financial industry insiders and the US government, only to have the rules of the game changed in the middle of the game. But don’t feel too bad for them, although they lost huge amounts of money, they still are worth several hundreds of millions of dollars, each.

Until his dying day in 2014, Nelson Bunker Hunt, who had once been the world’s wealthiest man, denied that he and his brother plotted to corner the global silver market.

Sure, back in 1980, Bunker, his younger brother Herbert, and other members of the Hunt clan owned roughly two-thirds of all the privately held silver on earth. But the historic stockpiling of bullion hadn’t been a ploy to manipulate the market, they and their sizable legal team would insist in the following years. Instead, it was a strategy to hedge against the voracious inflation of the 1970s—a monumental bet against the U.S. dollar.

Whatever the motive, it was a bet that went historically sour. The debt-fueled boom and bust of the global silver market not only decimated the Hunt fortune, but threatened to take down the U.S. financial system.

The panic of “Silver Thursday” took place over 35 years ago, but it still raises questions about the nature of financial manipulation. While many view the Hunt brothers as members of a long succession of white collar crooks, from Charles Ponzi to Bernie Madoff, others see the endearingly eccentric Texans as the victims of overstepping regulators and vindictive insiders who couldn’t stand the thought of being played by a couple of southern yokels.

In either case, the story of the Hunt brothers just goes to show how difficult it can be to distinguish illegal market manipulation from the old fashioned wheeling and dealing that make our markets work.

The Real-Life Ewings

Whatever their foibles, the Hunts make for an interesting cast of characters. Evidently, CBS thought so; the family is rumoured to be the basis for the Ewings, the fictional Texas oil dynasty of Dallas fame.

Sitting at the top of the family tree was H.L. Hunt, a man who allegedly purchased his first oil field with poker winnings and made a fortune drilling in east Texas. H.L. was a well-known oddball to boot, and his sons inherited many of their father’s quirks.

For one, there was the stinginess. Despite being the richest man on earth in the 1960s, Bunker Hunt (who went by his middle name), along with his younger brothers Herbert (first name William) and Lamar, cultivated an image as unpretentious good old boys. They drove old Cadillacs, flew coach, and when they eventually went to trial in New York City in 1988, they took the subway. As one Texas editor was quoted in the New York Times, Bunker Hunt was “the kind of guy who orders chicken-fried steak and Jello-O, spills some on his tie, and then goes out and buys all the silver in the world.”

Cheap suits aside, the Hunts were not without their ostentation. At the end of the 1970s, Bunker boasted a stable of over 500 horses and his little brother Lamar owned the Kansas City Chiefs. All six children of H.L.’s first marriage (the patriarch of the Hunt family had fifteen children by three women before he died in 1974) lived on estates befitting the scions of a Texas billionaire. These lifestyles were financed by trusts, but also risky investments in oil, real estate, and a host of commodities including sugar beets, soybeans, and, before long, silver.

The Hunt brothers also inherited their father’s political inclinations. A zealous anti-Communist, Bunker Hunt bankrolled conservative causes and was a prominent member of the John Birch Society, a group whose founder once speculated that Dwight Eisenhower was a “dedicated, conscious agent” of Soviet conspiracy. In November of 1963, Hunt sponsored a particularly ill-timed political campaign, which distributed pamphlets around Dallas condemning President Kennedy for alleged slights against the Constitution on the day that he was assassinated. JFK conspiracy theorists have been obsessed with Hunt ever since.

In fact, it was the Hunt brand of politics that partially explains what led Bunker and Herbert to start buying silver in 1973.

Hard Money

The 1970s were not kind to the U.S. dollar.

Years of wartime spending and unresponsive monetary policy pushed inflation upward throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s. Then, in October of 1973, war broke out in the Middle East, and an oil embargo was declared against the United States. Inflation jumped above 10%. It would stay high throughout the decade, peaking in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution at an annual average of 13.5% in 1980.

Over the same period of time, the global monetary system underwent a historic transformation. Since the first Roosevelt administration, the U.S. dollar had been pegged to the value of gold at a predictable rate of $35 per ounce. But in 1971, President Nixon, responding to inflationary pressures, suspended that relationship. For the first time in modern history, the paper dollar did not represent some fixed amount of tangible, precious metal sitting in a vault somewhere.

For conservative commodity traders like the Hunts, who blamed government spending for inflation and held grave reservations about the viability of fiat currency, the perceived stability of precious metal offered a financial safe harbour. It was illegal to trade gold in the early 1970s, so the Hunts turned to the next best thing.

As an investment, there was a lot to like about silver. The Hunts were not alone in fleeing to bullion amid all the inflation and geopolitical turbulence, so the price was ticking up. Plus, light-sensitive silver halide is a key component of photographic film. With the growth of the consumer photography market, new production from mines struggled to keep up with demand.

And so, in 1973, Bunker and Herbert bought over 35 million ounces of silver, most of which they flew to Switzerland in specifically designed aeroplanes guarded by armed Texas ranch hands. According to one source, Hunt’s purchases were big enough to move the global market.

But silver was not the Hunts’ only speculative venture in the 1970s. Nor was it the only one that got them into trouble with regulators.

Soy Before Silver

In 1977, the price of soybeans was rising fast. Trade restrictions on Brazil and growing demand from China made the legume a hot commodity, and both Bunker and Herbert decided to enter the futures market in April of that year.

A future is an agreement to buy or sell some quantity of a commodity at an agreed-upon price at a later date. If someone contracts to buy soybeans in the future (they are said to take the “long” position), they will benefit if the price of soybeans rises, since they have locked in the lower price ahead of time. Likewise, if someone contracts to sell (that’s called the “short” position), they benefit if the price falls since they have locked in the old, higher price.

While futures contracts can be used by soybean farmers and soy milk producers to guard against price swings, most futures are traded by people who wouldn’t necessarily know tofu from the cream cheese. As a de facto insurance contract against market volatility, futures can be used to hedge other investments or simply to gamble on prices going up (by going long) or down (by going short).

When the Hunts decided to go long in the soybean futures market, they went very, very long. Between Bunker, Herbert, and the accounts of five of their children, the Hunts collectively purchased the right to buy one-third of the entire autumn soybean harvest of the United States.

To some, it appeared as if the Hunts were attempting to corner the soybean market.

In its simplest version, a corner occurs when someone buys up all (or at least, most) of the available quantity of a commodity. This creates an artificial shortage, which drives up the price, and allows the market manipulator to sell some of his stockpile at a higher profit.

Futures markets introduce some additional complexity to the cornerer’s scheme. Recall that when a trader takes a short position on a contract, he or she is pledging to sell a certain amount of product to the holder of the long position. But if the holder of the long position just so happens to be sitting on all the readily available supply of the commodity under contract, the short seller faces an unenviable choice: go scrounge up some of the very scarce product in order to “make delivery” or just pay the cornerer a hefty premium and nullify the deal entirely.

In this case, the cornerer is actually counting on the shorts to do the latter, says Craig Pirrong, professor of finance at the University of Houston. If too many short sellers find that it actually costs less to deliver the product, the market manipulator will be stuck with warehouses full of inventory. Finance experts refer to selling the all the excess supply after building a corner as “burying the corpse.”

“That is when the price collapses,” explains Pirrong. “But if the number of deliveries isn’t too high, the loss from selling at the low price after the corner is smaller than the profit from selling contracts at the high price.”

Even so, when the Commodity Futures Trading Commission found that a single family from Texas had contracted to buy a sizable portion of the 1977 soybean crop, they did not accuse the Hunts of outright market manipulation. Instead, noting that the Hunts had exceeded the 3 million bushel aggregate limit on soybean holdings by about 20 million, the CFTC noted that the Hunt’s “excessive holdings threaten disruption of the market and could cause serious injury to the American public.” The CFTC ordered the Hunts to sell and to pay a penalty of $500,000.

Though the Hunts made tens of millions of dollars on paper while soybean prices skyrocketed, it’s unclear whether they were able to cash out before the regulatory intervention. In any case, the Hunts were none too pleased with the decision.

“Apparently the CFTC is trying to repeal the law of supply and demand,” Bunker complained to the press.

Silver Thursday

Despite the run in with regulators, the Hunts were not dissuaded. Bunker and Herbert had eased up on silver after their initial big buy in 1973, but in the fall of 1979, they were back with a vengeance. By the end of the year, Bunker and Herbert owned 21 million ounces of physical silver each. They had even larger positions in the silver futures market: Bunker was long on 45 million ounces, while Herbert held contracts for 20 million. Their little brother Lamar also had a more “modest” position.

By the new year, with every dollar increase in the price of silver, the Hunts were making $100 million on paper. But unlike most investors, when their profitable futures contracts expired, they took delivery. As in 1973, they arranged to have the metal flown to Switzerland. Intentional or not, this helped create a shortage of metal for industrial supply.

Naturally, the industrialists were unhappy. From a spot price of around $6 per ounce in early 1979, the price of silver shot up to $50.42 in January of 1980. In the same week, silver futures contracts were trading at $46.80. Film companies like Kodak saw costs go through the roof, while the British film producer, Ilford, was forced to lay off workers. Traditional bullion dealers, caught in a squeeze, cried foul to the commodity exchanges, and the New York jewellery house Tiffany & Co. took out a full-page ad in the New York Times slamming the “unconscionable” Hunt brothers. They were right to single out the Hunts; in mid-January, they controlled 69% of all the silver futures contracts on the Commodity Exchange (COMEX) in New York.

Source: New York Times

But as the high prices persisted, new silver began to come out of the woodwork.

“In the U.S., people rifled their dresser drawers and sofa cushions to find dimes and quarters with a silver content and had them melted down,” says Pirrong, from the University of Houston. “Silver is a classic part of a bride’s trousseau in India, and when prices got high, women sold silver out of their trousseaus.”

According to a Washington Post article published that March, the D.C. police warned residents of a rash of home burglaries targeting silver.

Unfortunately for the Hunts, all this new supply had a predictable effect. Rather than close out their contracts, short sellers suddenly found it was easier to get their hands on new supplies of silver and deliver.

“The main factor that has caused corners to fail [throughout history] is that the manipulator has underestimated how much will be delivered to him if he succeeds [at] raising the price to artificial levels,” says Pirrong. “Eventually, the Hunts ran out of money to pay for all the silver that was thrown at them.”

In financial terms, the brothers had a large corpse on their hands—and no way to bury it. This proved to be an especially big problem because it wasn’t just the Hunt fortune that was on the line. Of the $6.6 billion worth of silver the Hunts held at the top of the market, the brothers had “only” spent a little over $1 billion of their own money. The rest was borrowed from over 20 banks and brokerage houses.

At the same time, COMEX decided to crackdown. On January 7, 1980, the exchange’s board of governors announced that it would cap the size of silver futures exposure to 3 million ounces. Those in excess of the cap (say, by the tens of millions) were given until the following month to bring themselves into compliance. But that was too long for the Chicago Board of Trade exchange, which suspended the issue of any new silver futures on January 21. Silver futures traders would only be allowed to square up old contracts. Giving a guaranteed profit to everyone who was short in the silver market.

Predictably, silver prices began to slide. As the various banks and other firms that had backed the Hunt bullion binge began to recognize the tenuousness of their financial position, they issued margin calls, asking the brothers to put up more money as collateral for their debts. The Hunts, unable to sell silver lest they trigger a panic, borrowed even more. By early March, futures contracts had fallen to the mid-$30 range.

Matters finally came to a head-on March 25, when one of the Hunts’ largest backers, the Bache Group, asked for $100 million more in collateral. The brothers were out of cash, and Bache was unwilling to accept silver in its place, as it had been doing throughout the month. With the Hunts in default, Bache did the only thing it could to start recouping its losses: it starts to unload silver.

On March 27, “Silver Thursday,” the silver futures market dropped by a third to $10.80. Just two months earlier, these contracts had been trading at four times that amount.

The Aftermath

After the oil bust of the early 1980s and a series of lawsuits polished off the remainder of the Hunt brothers’ once historic fortune, the two declared bankruptcy in 1988. Bunker, who had been worth an estimated $16 billion in the 1960s, emerged with under $10 million to his name. That’s not exactly chump change, but it wasn’t enough to maintain his 500-plus stable of horses.

The Hunts almost dragged their lenders into bankruptcy too—and with them, a sizable chunk of the U.S. financial system. Over twenty financial institutions had extended over a billion dollars in credit to the Hunt brothers. The default and resulting collapse of silver prices blew holes in balance sheets across Wall Street. A privately orchestrated bailout loan from a number of banks allowed the brothers to start paying off their debts and keep their creditors afloat, but the markets and regulators were rattled.

In the words of then CFTC chief James Stone, the Hunts’ antics had threatened to punch a hole in the “financial fabric of the United States” like nothing had in decades. Writing about the entire episode a year later, Harper’s Magazine described Silver Thursday as “the first great panic since October 1929.”

The trouble was not over for the Hunts. In the following years, the brothers were dragged before Congressional hearings, got into a legal spat with their lenders, and were sued by a Peruvian mineral marketing company, which had suffered big losses in the crash. In 1988, a New York City jury found for the South American firm, levying a penalty of over $130 million against the Hunts and finding that they had deliberately conspired to corner the silver market.

Surprisingly, there is still some disagreement on that point.

Bunker Hunt attributed the whole affair to the political motives of COMEX insiders and regulators. Referring to himself later as “a favorite whipping boy” of an eastern financial establishment riddled with liberals and socialists, Bunker and his brother, Herbert, are still perceived as martyrs by some on the far-right. “Political and financial insiders repeatedly changed the rules of the game,” wrote the New American. “There is little evidence to support the ‘corner the market’ narrative.”

Though the Hunt brothers clearly amassed a staggering amount of silver and silver derivatives at the end of the 1970s, it is impossible to prove definitively that market manipulation was in their hearts. Maybe, as the Hunts always claimed, they just really believed in the enduring value of silver.

Or maybe, as others have noted, the Hunt brothers had no idea what they were doing. Call it the stupidity defence.

“They’re terribly unsophisticated,” an anonymous associated was quoted as saying of the Hunts in a Chicago Tribune article from 1989. “They make all the mistakes most other people make,” said another.

When the Hunts were dragged before the CFTC a few months after the crash, Commissioner David G. Gartner wondered out loud: “Do you think there’s any possibility that the Hunts are just having fun, just horsing around?”

In their civil trial against the South American mineral firm, the Hunt brothers’ decision to begin accepting delivery on their enormous holdings in silver futures was considered a red flag. A market participant would only take the actual metal, rather than cash in on highly profitable futures contracts if their plan was to remove the bullion from circulation and artificially inflate the price. That decision, it was argued, was consistent with market manipulation.

But one could argue that it is also consistent with having an irrational fixation on shiny metal and way more money than sense.

In his New York Times obituary in 2014, it was reported that towards the end of his life, Bunker Hunt had scrounged up enough to start buying horses again.

“I don’t know really know anything,” said Bunker, offering a synopsis of his horse trading strategy that could have just as easily applied to his entire career as an investor. “I am just trying to win a few races.”

The Rigged Danish Justice System

Yes, the Danish justice system was rigged before my win and judgement against Denmark at the European Court of Human Rights in 1989.

Yes, it was rigged by political prosecutions like mine. Yes, it was rigged because the Ministry of Justice was in charge of the police, prosecution, the appointment of the judges, the courts and prisons.

Even the former Minister of Justice for seven years and longest-serving member of the Danish Parliament, Erik Ninn-Hansen confirmed that the judges in Denmark were not independent – but under the dictatorship of the Ministry - he should know!

Rigged definition in most dictionaries: - manipulated or controlled by deceptive or dishonest means

Rigged is defined as something that is fixed in a dishonest way to guarantee the desired outcome.